Through the Looking-Glass: A Survival Guide for Absurd Times

Alice drifts back into my mind. Not the Alice I read as a child, soft and curious, but the Alice who steps through the mirror into a world where everything works backward. Time runs in reverse, logic flips upside down, and words lose their meaning. Yet she keeps going, adapting, and moving forward square by square across a chessboard landscape.

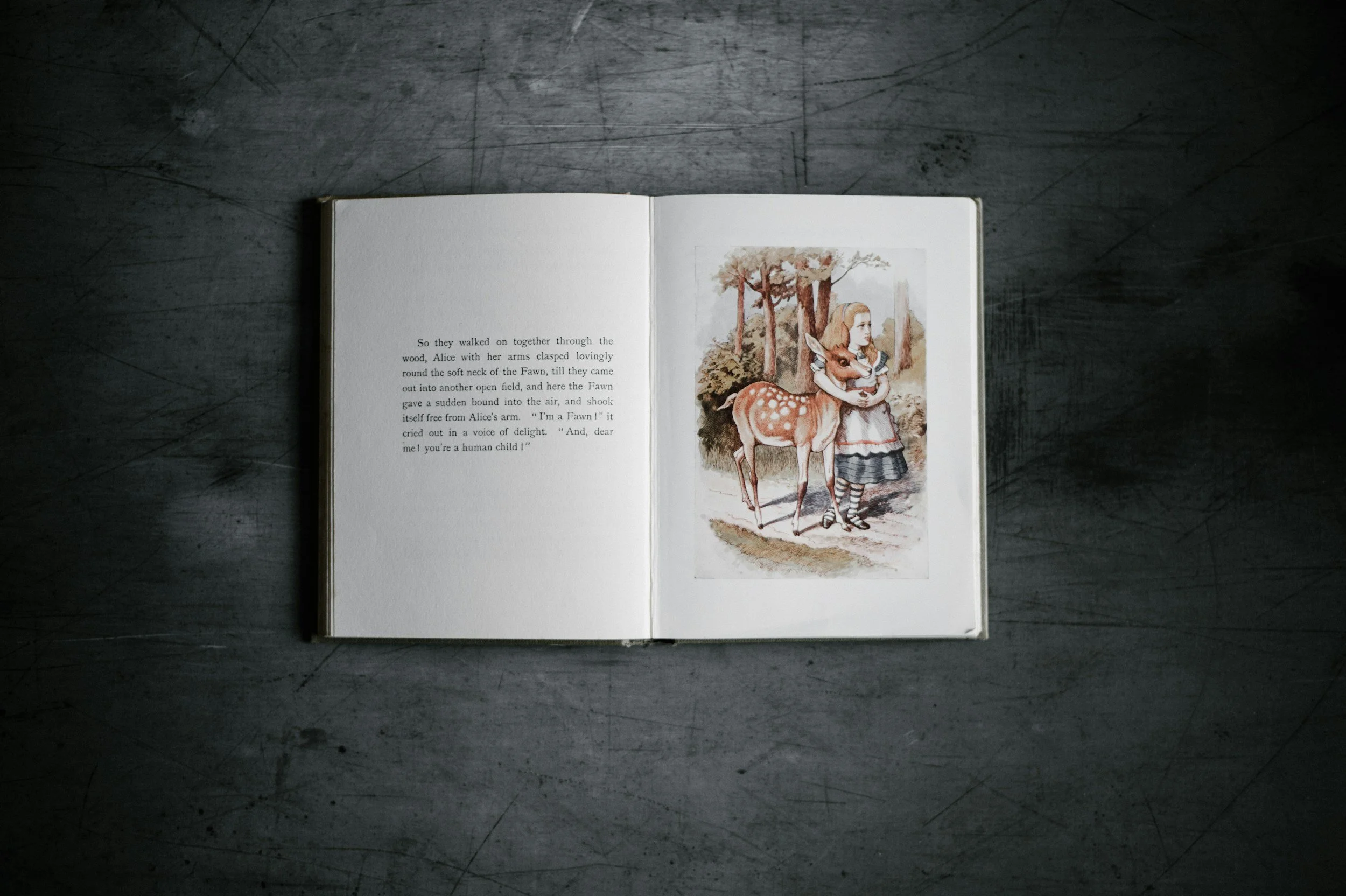

Reading Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass now, I realize this isn’t just a playful children’s story. Carroll is exploring something deeper, something that feels uncomfortably relevant: what happens when reality itself stops making sense?

I find myself returning to this looking-glass world because it anticipates our current moment with unsettling precision. We live in an era where authority figures contradict themselves daily, where social media feeds show us completely different versions of reality, and where language gets twisted and weaponized. Alice’s navigation of systematic absurdity offers more than metaphor. It offers a method. She shows me how to keep moving when nothing makes sense anymore.

Every day, we encounter people speaking in contradictions, in promises that are nothing, and in our own lives, consequences spiral, rules twist, and forces pull us along that we cannot name or resist.

What makes Alice special isn’t that she can fix the chaos. It’s that she refuses to let it freeze her in place. Throughout the story, she meets characters who deal with absurdity in different ways. The White Queen believes “six impossible things before breakfast,” just accepting delusion. Tweedledum and Tweedledee argue endlessly about nothing, stuck in circles. Humpty Dumpty insists words “mean just what I choose them to mean,” pretending he has control when he doesn’t.

Alice does none of these. Instead, she observes. She questions. She moves.

When the White Queen screams before pricking her finger, Alice objects: “But you haven’t pricked it yet.” She questions the rules even while playing by them. This isn’t naive faith that logic will win out. It’s something more powerful: trusting your own perception, even when everything around you says you’re wrong.

Watching Alice, I see what might be called “grounded presence”: she acknowledges that everything is distorted, but she stays connected to her own direct experience. The map may be replacing the territory, but she trusts what she actually sees and feels.

I am small. Limited by forces I can’t fully see. And yet, I move. I watch myself move. I pause. I measure. I step. I breathe. I notice the rhythm, the strange logic beneath the chaos, the small moments of order in all the spinning.

This careful attention becomes a form of resistance. Not the kind that fixes everything or brings back the old order, but the kind that says: I exist. I see what I see. The chaos doesn’t swallow me whole.

“ And still, somehow, moving, breathing, noticing: this is proof that I exist. That I am. That the chaos does not swallow me.”

The looking-glass world is structured as a chess game, with Alice as a pawn trying to become a queen. The metaphor works perfectly: you can only move in certain ways, the rules are strict but make no real sense, and you can’t see the whole board.

This tension between rigid structure and total confusion mirrors our digital world. Every headline, every news feed, every overheard conversation is shaped by invisible algorithms that decide what we see. Meanwhile, our shared sense of reality falls apart. We move through systems we can’t fully understand, square by square, finding footholds wherever we can.

The looking-glass world captured Victorian England’s anxiety about rapid industrialization and social change. We’re facing similar dizziness today, just at digital speed and scale. Alice’s response still teaches us something important: she doesn’t reject the game or pretend she’s above it. She plays, square by square, fully aware of how absurd it all is.

And for a moment, long enough to catch our breath, long enough to meet the world on its own twisted terms, the ground feels solid.

Philosopher Albert Camus wrote about absurdity as the clash between our human need for meaning and the world’s “unreasonable silence.” But the looking-glass world isn’t silent. It’s screaming with contradictory meanings. The absurdity isn’t about having no meaning, but having too many meanings that cancel each other out.

Alice faces this throughout the story. When she finally reaches the Eighth Square and becomes a Queen, she expects everything to make sense. Instead, the celebration feast dissolves into chaos: food that talks back, guests that disappear, a world that refuses to come together even at what should be her moment of triumph. Yet the story continues. Alice continues.

This is what I take from Carroll: meaning can be temporary, incomplete, and still be enough. The ground beneath our feet doesn’t have to be permanent to be real. I can acknowledge my limits, see the absurdity clearly, and keep moving anyway. I can reclaim some agency, even if partial. I can find meaning, even if temporary. I can exist, even if it feels fragile.

The absurdity isn’t just something weird that happens to us sometimes. It’s the basic condition of being alive right now. It demands that we pay attention. It demands that we fully inhabit ourselves in a world that won’t stay still. We can’t skim past it. We can’t ignore it. We have to step into it, even when it threatens to knock us over.

The absurdity isn’t just something weird that happens to us sometimes. It’s the basic condition of being alive right now.

Carroll wrote Through the Looking-Glass as a sequel to Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, but the two books work differently. Wonderland is chaotic and dreamlike, where anything can happen. The looking-glass world has strict rules and systems, but those rules flip meaning upside down instead of creating order. That’s what makes it more unsettling. More relevant.

We don’t live in a world without rules. We live in a world where rules multiply endlessly, contradict each other, and serve powerful forces we can’t fully see. Like Alice, I am small and limited, moving across a board whose full logic I cannot grasp.

Yet there’s a strange freedom in this. Freedom in admitting my limits and moving forward anyway. Freedom in paying close attention, in fully inhabiting myself on purpose, in looking around corners even when I can’t see what’s there.

Alice doesn’t escape the looking-glass world by solving it. She wakes up, but only after moving through it completely, square by square, fully present to how impossible it all is.

The lesson isn’t that absurdity can be overcome, but that it can be inhabited. The world may twist and contort, but I move. I adapt. I reclaim agency, partial though it may be. I find meaning, though it is temporary. I exist, fragile though it feels.

The looking-glass world isn’t a fantasy to escape into. It’s a survival guide for the world I already occupy. And Alice, careful and persistent, shows me how to move through it: step by step, square by square, noticing everything, surrendering nothing, surviving.