Misunderstood

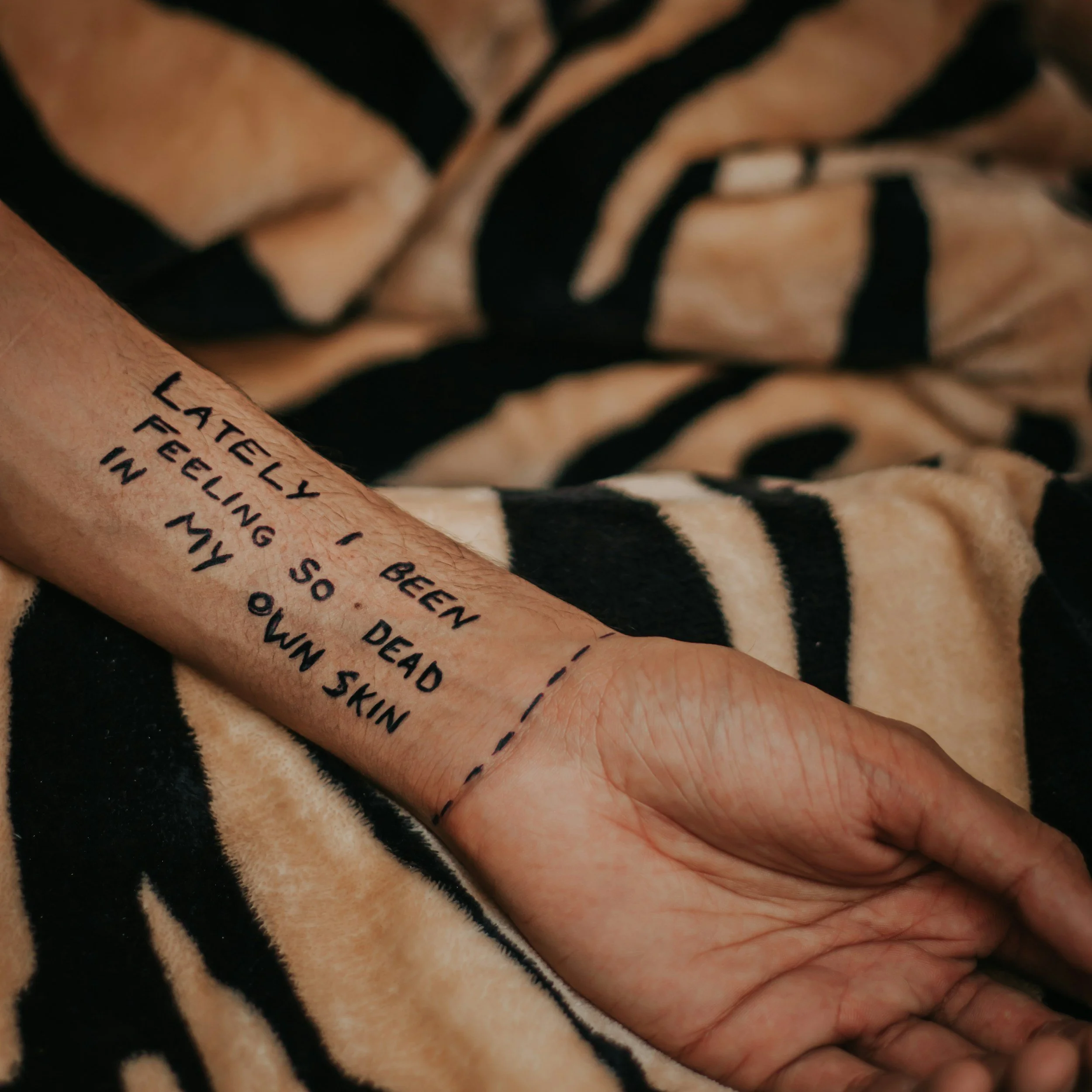

When we hear the words mental illness, an image usually arrives before thought. It happens quickly, almost involuntarily: a figure in a hospital corridor, a television character speaking to no one in particular, a headline that links instability with danger and offers fear as an explanation. Sometimes the picture is emptier than that: a person alone, a room without sound, a life stalled in its own shadow.

It prefers the spectacle: the violent outlier, the brilliant but unstable mind, the ruined figure whose suffering becomes narrative shorthand.

These images are learned. We collect them without noticing. They come from screens and stories, from the shorthand of news coverage, from the roles written for entertainment, from the language people reach for when they are unsure what they are seeing. Over time, they settle. They form a quiet consensus about what mental illness is supposed to look like.

The question is how much of that consensus is true.

“...a headline that links instability with danger and offers fear as an explanation”

Mental illness does not announce itself in every case. It does not constantly interrupt the day. Often it exists alongside ordinary life: someone sits at a table, nodding, answering questions, while panic moves steadily beneath the surface. Someone goes to work carrying a heaviness no one else registers. Someone survives trauma and learns to appear composed. Nothing dramatic happens. Nothing visible breaks. And yet the experience is constant.

The media rarely sticks with these versions. It prefers the spectacle: the violent outlier, the brilliant but unstable mind, the ruined figure whose suffering becomes narrative shorthand. These stories hold attention, but they also simplify. They turn complexity into posture. They replace curiosity with distance.

These images are learned. We collect them without noticing.

The way mental illness is portrayed matters because stories teach us how to look. They suggest what deserves alarm and what can be ignored, shape what we believe about other people and, eventually, about ourselves. When the dominant images are extreme, quieter realities become illegible.

Most lives do not unfold at the edge of crisis. They unfold in persistence, in effort, in people learning how to keep going while carrying something unseen.

There is no single shape for mental illness. It does not belong to a costume, a diagnosis scene, or a dramatic turning point. It appears inside competence and collapse, inside strength and fatigue, resisting reduction to a single story.

“If we begin with attention instead of assumption, something shifts. The story grows quieter but more accurate, more human.”

To look at media portrayals, then, is not only to critique representation but to examine what we have been trained to notice and trained to miss, to ask whose experiences feel familiar and whose feel unbelievable, to recognize how easily we accept a narrow version of reality when it is repeated often enough.

If we begin with attention instead of assumption, something shifts. The story grows quieter but more accurate, more human.

In that quiet, there is room for a different understanding: one that does not depend on spectacle, fear, or simplification, but on seeing people as they actually live.