The Quiet Stones of Mood: Understanding Toxic Stress, Trauma, and the Mind

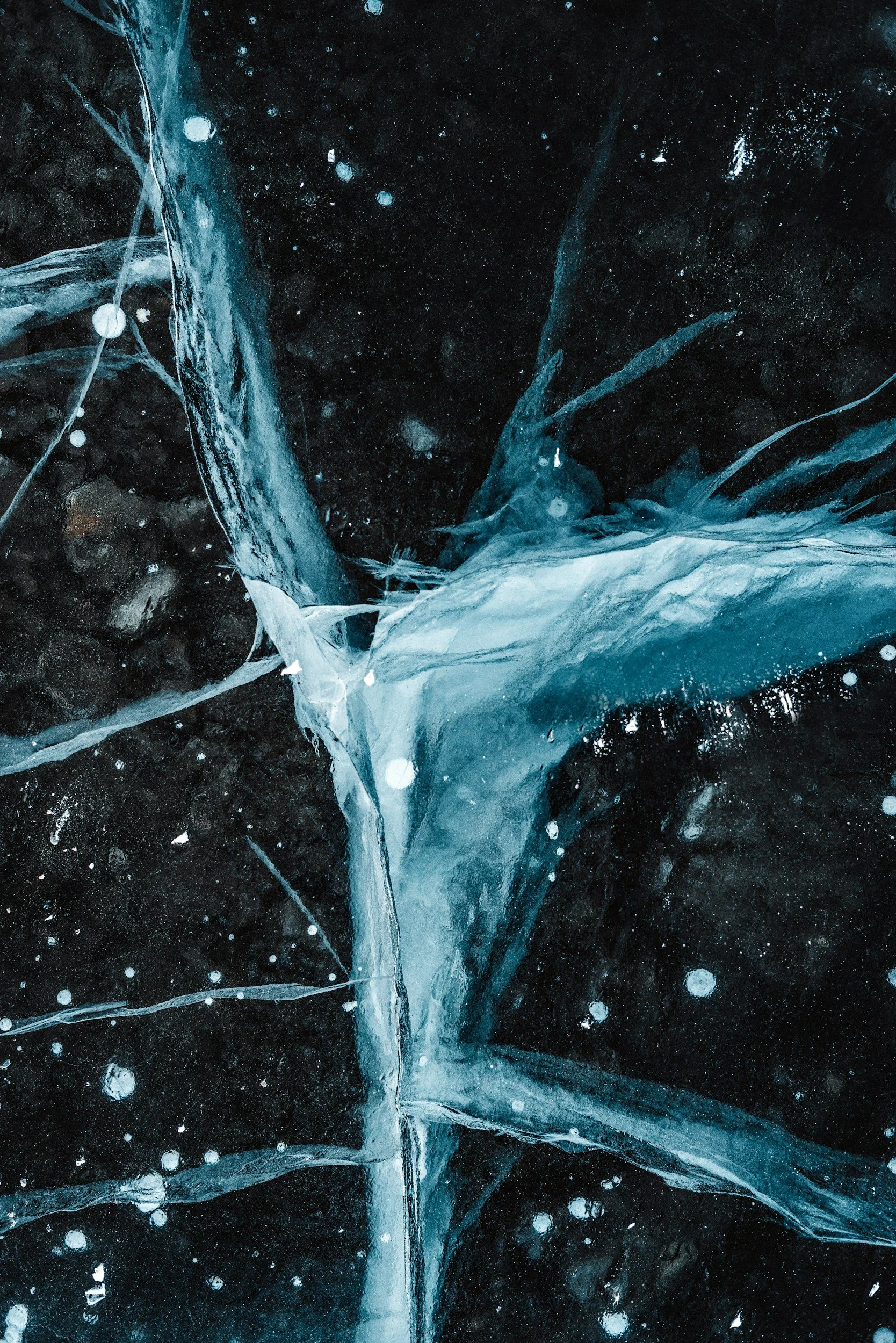

Mood is like a stone carried quietly in the pocket. Sometimes unnoticed. Sometimes unbearably heavy. You carry it through grocery stores and dinner parties, through ordinary Tuesdays that feel like wading through water. Depression, bipolar disorder, and other mood disorders are not clinical labels so much as they are lived experiences. Shaped by stress. Amplified by trauma. Encoded in the habitual ways we think and interpret the world. The mind records both threat and vulnerability the way a body records a scar. It translates experience into patterns of thought and behavior that may feel unshakable.

From childhood onward, the mind negotiates an invisible web of pressures: biological rhythms, social expectations, cognitive habits, emotional responses, and psychological frameworks. Toxic stress, the prolonged and unrelenting strain that keeps the body and brain on high alert, plays a central role in shaping mood. Experiences such as childhood trauma, abuse, neglect, household instability, poverty, and discrimination accumulate over time. They build neural pathways that push the mind toward hypervigilance, self-criticism, and despair. These experiences do not operate in isolation. They interact with genetics, temperament, and social environment to influence how stress is encoded in the brain and expressed in behavior.

Automatic thoughts are subtle signals of this burden. These instantaneous, habitual mental reactions pass almost unnoticed, yet they shape the way we perceive ourselves, the world, and the future. I am worthless. I will always fail. Nothing will ever change. When negative, automatic thoughts become cognitive distortions that exaggerate reality, distort perception, and bias attention toward threat or failure. Rumination, the obsessive and repetitive focus on problems without resolution, locks the mind into cycles of self-reproach and hopelessness. The same thoughts, circling. The same conclusions, reached again and again at three in the morning. This looping pattern can persist even when the original danger has passed, maintaining vulnerability to depressive episodes and intensifying emotional suffering.

Learned helplessness helps explain how early experiences of uncontrollable stress leave the mind prone to despair. A child learns that crying brings no comfort. An adult learns that effort changes nothing. When negative events are interpreted as internal, stable, and global, the mind assumes that control is impossible, contributing to the onset and persistence of depression. Hopelessness theory extends this idea, suggesting that the combination of cognitive vulnerability and adverse life events produces the feeling that change is unattainable. These cognitive patterns interact with memory, attention, and perception. People with depression are more likely to focus attention on negative stimuli, interpret ambiguous events pessimistically, and recall disproportionately more negative memories. A compliment slides past. A criticism lodges deep. This pattern reinforces low mood and disengagement.

Bipolar disorder introduces another layer of complexity. Mania can feel sudden, intense, and intoxicating, a rush of invincibility and sleepless clarity, only to be followed by the tidal pull of depression. The crash comes. It always comes. Childhood trauma amplifies these oscillations, accelerating onset, increasing suicide risk, and contributing to co-occurring substance misuse. In this sense, toxic stress acts as both a trigger and an amplifier, sensitizing the nervous system to emotional extremes and influencing the frequency and severity of mood episodes. Stressful life events, both chronic and acute, are strongly linked to relapse and symptom severity, illustrating how environmental and psychological factors interact with underlying biological vulnerabilities.

Stress is rarely purely personal. Poverty, discrimination, racism, sexism, and homophobia form persistent and chronic stressors that compound vulnerability to mood disorders. Material hardship, lack of medical care, unstable housing, and food insecurity are linked to higher rates of depression, while everyday discrimination contributes to increased depressive symptoms. The microaggressions accumulate. The doors that do not open. The assumptions made before you speak. Intersectionality magnifies this effect. Overlapping marginalized identities, such as race, sexual orientation, or gender identity, increase exposure to adversity while simultaneously limiting access to protective resources. Living under these pressures is a form of toxic stress that reshapes how the mind perceives threat, loss, and possibility, leaving deep imprints on emotion, cognition, and behavior.

The psychological consequences of toxic stress extend beyond mood. Attention narrows to potential danger, memory encodes threat disproportionately, and interpretation of social and environmental cues skews toward pessimism or self-blame. A door slams and the body tenses. A tone of voice and the mind prepares for attack. These cognitive biases are adaptive in a chronically threatening environment, keeping the individual alert, but they are maladaptive in contexts where threat is no longer present. In this way, the mind’s patterns reflect survival strategies that have gone astray, maintaining cycles of depression or mood dysregulation long after the original stressor has passed. The danger is gone but the body does not know this.

I remember the first time I recognized rumination for what it was. I was standing in my kitchen at dawn, coffee going cold in my hand, running through the same mental catalogue of failures I had been running through for weeks. The light changed outside. I was still standing there. Two hours had passed. I had not moved.

Awareness of these processes is a fragile form of hope. Recognizing patterns of rumination, cognitive distortion, and attentional bias does not erase pain or remove the memory of trauma, but it allows for a degree of agency. Knowledge of how the mind interprets and reacts to stress creates space between thought and reaction, between experience and identity. Understanding that automatic thoughts are habitual rather than absolute can shift the relationship to them, enabling strategies to interrupt rumination, reframe negative interpretations, and seek adaptive coping mechanisms.

Mood disorders are neither simple nor singular. They emerge at the intersection of life experience, stress, biology, and thought. They are amplified by trauma, encoded in automatic thought patterns, and shaped by the broader social context. The effects of toxic stress are cumulative and pervasive, influencing the onset, course, and severity of mood disorders while interacting with other risk factors. Recognizing these forces allows for compassion toward the mind’s vulnerability and toward the resilience that persists despite adversity.

Ultimately, living with a mood disorder in a world shaped by toxic stress is to inhabit two realities at once: the visible life and the internal one, the external expectations and the persistent shadows of experience. You smile at the right moments. You answer when spoken to. Inside, something else is happening entirely. Treatment, therapy, social support, and self-awareness can help navigate these overlapping realities, but understanding the full context, the interaction of stress, trauma, cognition, and society, is essential. Mood disorders are not failures of will or character. They are the mind’s response to the environment, magnified by the cumulative burden of stress and adversity. Acknowledging this reality is not resignation. It is clarity. And clarity, in turn, allows living with the weight of stress without being entirely defined by it.

The stone remains in the pocket. Some days it is lighter. Some days, you forget it is there at all. But you learn to walk with it, to know its weight without letting it determine every step. This is not triumph. This is simply what it means to continue.